There is a game. A computer game. It has been with me since tweenhood, in five different incarnations. Civilization I by Sid Meier hit the shelves back in 1991, and its latest descendant, Civilization V, came out late 2010. The object of the game is to build your own civilization, starting from a single settler at the advent of agriculture back in 4.000 BC, ending with winning the race to the stars sometime in the future. You play one of the great civilizations of our world, from the Babylonians to the United States of America, and try to look past the slight anachronism of playing an immortal George Washington starting his exploits with mud huts and adzes.

At the beginning of the game, all you have to your name are two units; an axe-wielding group of warriors, and some pretty biblical-looking settlers.

And so it begins. Your settlers found a town, you research new technologies, your workers begin developing nearby resources, you found a religion and pray to your gods that the first civilization you meet won’t be headed by Genghis Khan.

It’s an addictive game, and no matter how pacifistic you are in real life, it’s easy to get carried away and exploit and terrorize those less powerful than you if you get to the top of the power pyramid (though it’s a bit hard to justify if you’re playing the Indians under Gandhi). But if you’re too eager to declare war on your less advanced neighbours, you’ll soon get all the other leaders against you, which works as a deterrent unless you actually want to genocide everyone else. Sometimes, I have had to make a conscious choice: In this playthrough, I will not attack anyone unless they declare war on me first. Self-imposed restrictions like this makes for a tougher, though more rewarding, game. Especially when those pesky Indians (with their total lack of population control) start settling close to your cities, and your trigger finger starts to itch, because you feel that this should be your territory. But when your civilization manages to build the United Nations and all the other world leaders hail you as a paragon of peace and you win a diplomatic victory, the hardest of them all, you do feel a warm glow of pride inside.

Barbarians

In any playthrough, even the peace-abiding ones, there are some opponents that you can attack without any guilt whatsoever. The barbarians. Described in the game manual as «roving bands of villains who hate civilization and everything that goes with it», they are portrayed with fierce scowls and horned helmets. Whenever you find a barbarian encampment, it has to be mown to the ground, or they will soon be at your gates.

The concept of barbarians started with the Greeks. To them, all the people outside their highly developed city states, had strange and harsh languages. They spoke «bar-bar», plain nonsense. It’s a small relief to know that universal justice gave the Greeks proper payback for this, by giving the world the expression «That’s Greek to me» (Of course I love you, Greeks. I know you know that.) Since then, it’s become a term for the stateless, the uncivilized, the Other, as well as for this guy.

Killing barbarians in the game doesn’t worry me. After all, I know that within the framework of the game, they can not be reasoned with, they are intent on my destruction, and they have absolutely no culture. What has started to worry me is the fact that they are part of the game at all. Where in the world do we find these people? «who hate civilization and everything that goes with it»?

Where it’s convenient for us.

Settlers

Just now, I’m sitting in Ramallah Café in the West Bank. The Palestinian Territories are not recognized as a state. In the logic of one of my favourite computer games of all time, the friendly people sitting here drinking the best Arabic coffee in town and smoking water pipes, are all barbarians. This culture, where it’s hard to walk the streets without getting at least three or four «Welcome!» thrown your way, would be equivalent to warmongering brutes. In the game, when you settle a new town, there has to be more than three spaces between it and the neighbouring town, and you can never ever build a settlement within the cultural boundaries of another civilization, even when you are at war with them. But barbarians, those nomadic bastards, are exempt from this rule. They don’t own the land they live on – the very notion would be absurd.

Here, new settlements pop up constantly within the Palestinian Territories. Settlers, some of them ultraorthodox Jews with the same costume design as their namesakes in Civilization, go all over this place and click the «FOUND CITY HERE»-button, even if a Palestinian city is in the very next square. The only way for this to be possible is if the Israelis have access to some pretty neat cheat codes, or if the Palestinians are recognized as barbarians.

It’s illegal to establish these settlements under Israeli law, yet they still keep coming. The story of this land belonging to the tribes of Israel is a strong one, and through this religious motivation (though some have a purely economical motive), the most fertile land in the Palestinian territories is taken away. And the hate that some of these settlers have towards their Palestinian neighbours is only understandable if these neighbours are viewed as less than human. A Norwegian I met down here, working with an international presence-NGO called EAPPI, told me some pretty disturbing stories that are just the icing of the cake.

– A settlement had been established just next to an area where Palestinian children pass by to go to school. Every day, settlers would gather to throw stones and insults at the passing kids. The kids were protected by Israeli soldiers, but they wouldn’t always be too diligent or follow them only parts of the way. My friend and other internationals were there to ensure that the kids were taken care of all the way.

– Near the city of Jayus, an illegal settlement has been placed on top of a hill. Under the hill is a Palestinian school. Twice every week, the settlers would drop all their sewage down the hill, leaving it to float in the schoolyard.

And all over the place, settlers are burning and destroying Palestinian olive groves, with little or no resistance from Israeli military. The breaking off of olive branches is a common occurence. Olive branches, traditionally seen as offerings of peace, have become offerings of hatred.

But nothing compares to the situation in the old city of Hebron.

Barbarians at the gate?

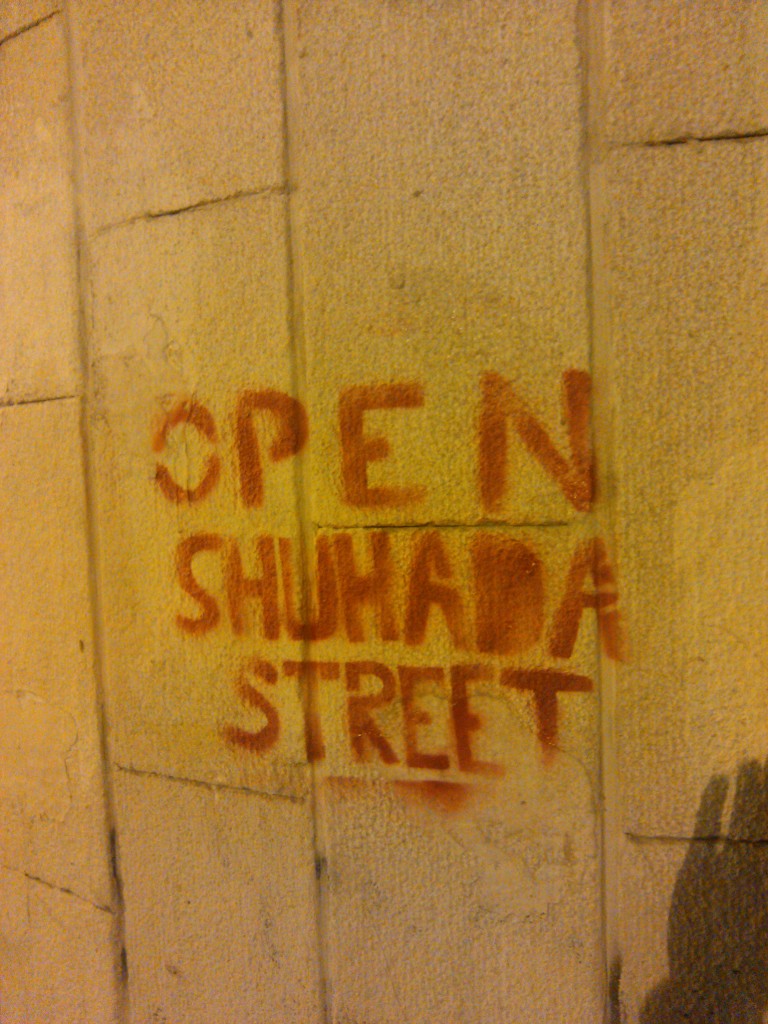

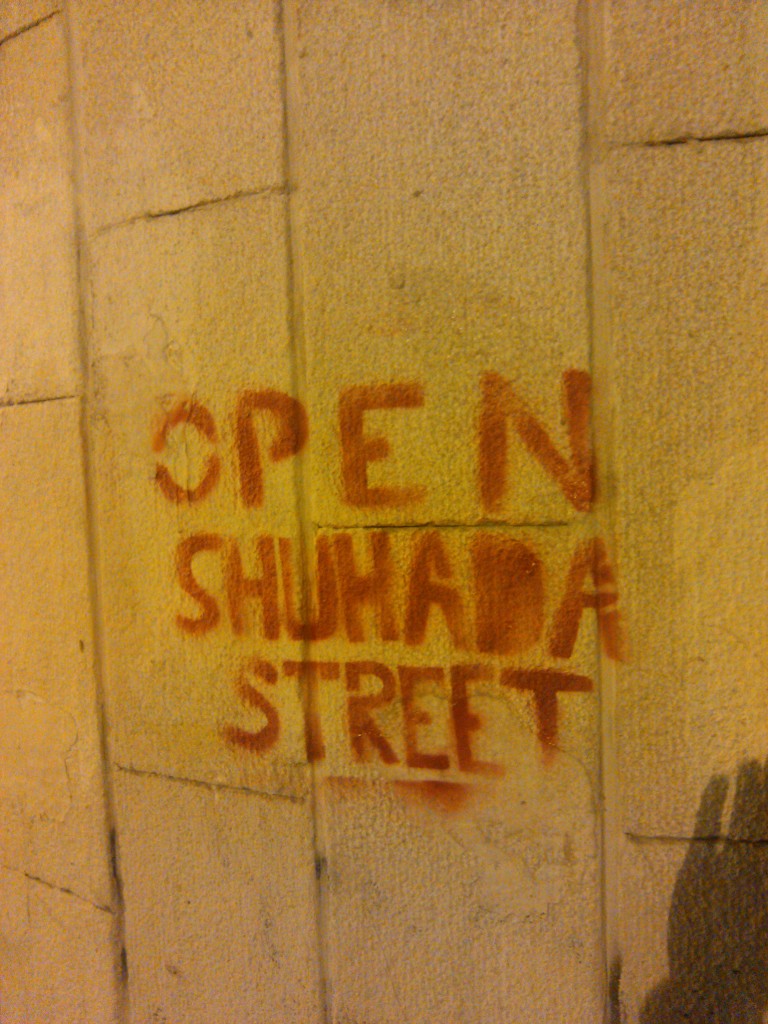

In the 90s, just after the Oslo peace accords, a few orthodox Jews came to Hebron. They promised that they did not intend to stay, but soon enough they had established a settlement smack dab in the middle of the Old City. It kept growing, taking over Shuhada Street, a main thoroughfare and a bustling marketplace, which is now closed to Palestinians. Now there are 500 settlers living there, protected by 2000 soldiers.

Last Saturday I travelled there. I came to the Old City just in time for the settler tour. Once every Saturday the settlers march through the city, protected by a living shield of soldiers, to underline their right to live and expand here. This time, however, it didn’t happen. Tensions about the Gaza crisis had made a group of kids throw stones from the top of a steep road, making it unsafe for the settlers to start their walk. Behind a fortified gate, we could see several soldiers gathering together, pressure increasing, like a champagne bottle cork just about to blow.

And then: Pow! They ran out in an organized line to catch the kids, shooting sound bombs and brandishing fully automatic weapons. The kids replied with fireworks, lighting up the sky, before running for shelter. The soldiers retreated, into the gate. Waiting. Then, more stones and fireworks. Pow! The soldiers ran out again. Sound bomb. Retreat. Stones. Pow! Sound bomb. Retreat. Fireworks. Pow! A never-ending game of cat and mouse.

Then tear gas was on the table, filling the air with its awful stench. I suddenly understood why so many people carried onions around, one eye-watering substance to ward off another. We were away from the main part of it then, in a side street, the smell of tear gas in the air, the occasional stray stone thudding against the protective metal plates covering the closed stalls at our backs. One of the Palestinians that were with us then suddenly chose that particular moment to look at me and say, with a friendly smile, «Welcome!». Then, both becoming aware of the absurdity of that comment, we started to laugh.

What is happening to protests and demonstrations all over the West Bank, is no laughing matter, however. Yesterday, a 28 year old man, a police officer from Nabu Saleh, died from the wounds that were inflicted on him the day before. The occasion was a demonstration leading to rock throwing from the Palestinians and live bullets from the soldiers.

Endgame

The world at large is still treating the Palestinians as Civilization treats barbarians. I mean, I wouldn’t stand a chance if I treated any other actual player like this during a game. Even George Washington would stop trading with me. With this in mind, it is good to see that even when some shout out and ask for the demolishing and ethnic cleansing of Gaza, and others sit down outdoors in couches to watch the bombing as if it actually was a game, the number of Israelis clamoring for peace and co-existence is increasing. What I saw in Hebron was insanity, pure and simple. A hopeless microcosm of the entire situation. The only thing that can stop it, I believe, is that people here, like King Saul did back in the day, let the scales fall from their eyes, and work to stop the dehumanization of their neighbours. The world must accept and fully understand, not only in theory but in practice, that Palestine is a civilization in its own right. That a game is unwinnable when we follow different rule books.

When the idea of the barbarian is purged from our minds, when the temptation to abuse power is replaced by a conscious choice to say «no», when the power of «Welcome!» overturns the power of the tear gas canister, then, and only then, can we hope to win a diplomatic victory.

The hardest, yet most rewarding, victory of them all.

There is a game. A computer game. It has been with me since tweenhood, in five different incarnations. Civilization I by Sid Meier hit the shelves back in 1991, and its latest descendant, Civilization V, came out late 2010. The object of the game is to build your own civilization, starting from a single settler at the advent of agriculture back in 4.000 BC, ending with winning the race to the stars sometime in the future. You play one of the great civilizations of our world, from the Babylonians to the United States of America, and try to look past the slight anachronism of playing an immortal George Washington starting his exploits with mud huts and adzes.

At the beginning of the game, all you have to your name are two units; an axe-wielding group of warriors, and some pretty biblical-looking settlers.

And so it begins. Your settlers found a town, you research new technologies, your workers begin developing nearby resources, you found a religion and pray to your gods that the first civilization you meet won’t be headed by Genghis Khan.

It’s an addictive game, and no matter how pacifistic you are in real life, it’s easy to get carried away and exploit and terrorize those less powerful than you if you get to the top of the power pyramid (though it’s a bit hard to justify if you’re playing the Indians under Gandhi). But if you’re too eager to declare war on your less advanced neighbours, you’ll soon get all the other leaders against you, which works as a deterrent unless you actually want to genocide everyone else. Sometimes, I have had to make a conscious choice: In this playthrough, I will not attack anyone unless they declare war on me first. Self-imposed restrictions like this makes for a tougher, though more rewarding, game. Especially when those pesky Indians (with their total lack of population control) start settling close to your cities, and your trigger finger starts to itch, because you feel that this should be your territory. But when your civilization manages to build the United Nations and all the other world leaders hail you as a paragon of peace and you win a diplomatic victory, the hardest of them all, you do feel a warm glow of pride inside.

Barbarians

In any playthrough, even the peace-abiding ones, there are some opponents that you can attack without any guilt whatsoever. The barbarians. Described in the game manual as «roving bands of villains who hate civilization and everything that goes with it», they are portrayed with fierce scowls and horned helmets. Whenever you find a barbarian encampment, it has to be mown to the ground, or they will soon be at your gates.

The concept of barbarians started with the Greeks. To them, all the people outside their highly developed city states, had strange and harsh languages. They spoke «bar-bar», plain nonsense. It’s a small relief to know that universal justice gave the Greeks proper payback for this, by giving the world the expression «That’s Greek to me» (Of course I love you, Greeks. I know you know that.) Since then, it’s become a term for the stateless, the uncivilized, the Other, as well as for this guy.

Killing barbarians in the game doesn’t worry me. After all, I know that within the framework of the game, they can not be reasoned with, they are intent on my destruction, and they have absolutely no culture. What has started to worry me is the fact that they are part of the game at all. Where in the world do we find these people? «who hate civilization and everything that goes with it»?

Where it’s convenient for us.

Settlers

Just now, I’m sitting in Ramallah Café in the West Bank. The Palestinian Territories are not recognized as a state. In the logic of one of my favourite computer games of all time, the friendly people sitting here drinking the best Arabic coffee in town and smoking water pipes, are all barbarians. This culture, where it’s hard to walk the streets without getting at least three or four «Welcome!» thrown your way, would be equivalent to warmongering brutes. In the game, when you settle a new town, there has to be more than three spaces between it and the neighbouring town, and you can never ever build a settlement within the cultural boundaries of another civilization, even when you are at war with them. But barbarians, those nomadic bastards, are exempt from this rule. They don’t own the land they live on – the very notion would be absurd.

Here, new settlements pop up constantly within the Palestinian Territories. Settlers, some of them ultraorthodox Jews with the same costume design as their namesakes in Civilization, go all over this place and click the «FOUND CITY HERE»-button, even if a Palestinian city is in the very next square. The only way for this to be possible is if the Israelis have access to some pretty neat cheat codes, or if the Palestinians are recognized as barbarians.

It’s illegal to establish these settlements under Israeli law, yet they still keep coming. The story of this land belonging to the tribes of Israel is a strong one, and through this religious motivation (though some have a purely economical motive), the most fertile land in the Palestinian territories is taken away. And the hate that some of these settlers have towards their Palestinian neighbours is only understandable if these neighbours are viewed as less than human. A Norwegian I met down here, working with an international presence-NGO called EAPPI, told me some pretty disturbing stories that are just the icing of the cake.

– A settlement had been established just next to an area where Palestinian children pass by to go to school. Every day, settlers would gather to throw stones and insults at the passing kids. The kids were protected by Israeli soldiers, but they wouldn’t always be too diligent or follow them only parts of the way. My friend and other internationals were there to ensure that the kids were taken care of all the way.

– Near the city of Jayus, an illegal settlement has been placed on top of a hill. Under the hill is a Palestinian school. Twice every week, the settlers would drop all their sewage down the hill, leaving it to float in the schoolyard.

And all over the place, settlers are burning and destroying Palestinian olive groves, with little or no resistance from Israeli military. The breaking off of olive branches is a common occurence. Olive branches, traditionally seen as offerings of peace, have become offerings of hatred.

But nothing compares to the situation in the old city of Hebron.

Barbarians at the gate?

In the 90s, just after the Oslo peace accords, a few orthodox Jews came to Hebron. They promised that they did not intend to stay, but soon enough they had established a settlement smack dab in the middle of the Old City. It kept growing, taking over Shuhada Street, a main thoroughfare and a bustling marketplace, which is now closed to Palestinians. Now there are 500 settlers living there, protected by 2000 soldiers.

Last Saturday I travelled there. I came to the Old City just in time for the settler tour. Once every Saturday the settlers march through the city, protected by a living shield of soldiers, to underline their right to live and expand here. This time, however, it didn’t happen. Tensions about the Gaza crisis had made a group of kids throw stones from the top of a steep road, making it unsafe for the settlers to start their walk. Behind a fortified gate, we could see several soldiers gathering together, pressure increasing, like a champagne bottle cork just about to blow.

And then: Pow! They ran out in an organized line to catch the kids, shooting sound bombs and brandishing fully automatic weapons. The kids replied with fireworks, lighting up the sky, before running for shelter. The soldiers retreated, into the gate. Waiting. Then, more stones and fireworks. Pow! The soldiers ran out again. Sound bomb. Retreat. Stones. Pow! Sound bomb. Retreat. Fireworks. Pow! A never-ending game of cat and mouse.

Then tear gas was on the table, filling the air with its awful stench. I suddenly understood why so many people carried onions around, one eye-watering substance to ward off another. We were away from the main part of it then, in a side street, the smell of tear gas in the air, the occasional stray stone thudding against the protective metal plates covering the closed stalls at our backs. One of the Palestinians that were with us then suddenly chose that particular moment to look at me and say, with a friendly smile, «Welcome!». Then, both becoming aware of the absurdity of that comment, we started to laugh.

What is happening to protests and demonstrations all over the West Bank, is no laughing matter, however. Yesterday, a 28 year old man, a police officer from Nabu Saleh, died from the wounds that were inflicted on him the day before. The occasion was a demonstration leading to rock throwing from the Palestinians and live bullets from the soldiers.

Endgame

The world at large is still treating the Palestinians as Civilization treats barbarians. I mean, I wouldn’t stand a chance if I treated any other actual player like this during a game. Even George Washington would stop trading with me. With this in mind, it is good to see that even when some shout out and ask for the demolishing and ethnic cleansing of Gaza, and others sit down outdoors in couches to watch the bombing as if it actually was a game, the number of Israelis clamoring for peace and co-existence is increasing. What I saw in Hebron was insanity, pure and simple. A hopeless microcosm of the entire situation. The only thing that can stop it, I believe, is that people here, like King Saul did back in the day, let the scales fall from their eyes, and work to stop the dehumanization of their neighbours. The world must accept and fully understand, not only in theory but in practice, that Palestine is a civilization in its own right. That a game is unwinnable when we follow different rule books.

When the idea of the barbarian is purged from our minds, when the temptation to abuse power is replaced by a conscious choice to say «no», when the power of «Welcome!» overturns the power of the tear gas canister, then, and only then, can we hope to win a diplomatic victory.

The hardest, yet most rewarding, victory of them all.

Legg igjen en kommentar